I'm establishment AF and I still support the right to protest

To be clear, I don’t want to talk about this. I don’t want to think about it. I want to pull the covers over my head, like I’m a little kid, until all of this is over.

I want the pavers laid back in the ground they were prised from. I want the filth and desecration cleansed from the marae. I want the debris swept - the burnt, the broken - and the ground to be blessed. I just want to heal.

But we’ve had this conversation forced on us. Decisions will be made in the next days or weeks, in this time we are hurting; but they need to be thought through well, so they serve us in the time beyond. That means we need to talk now.

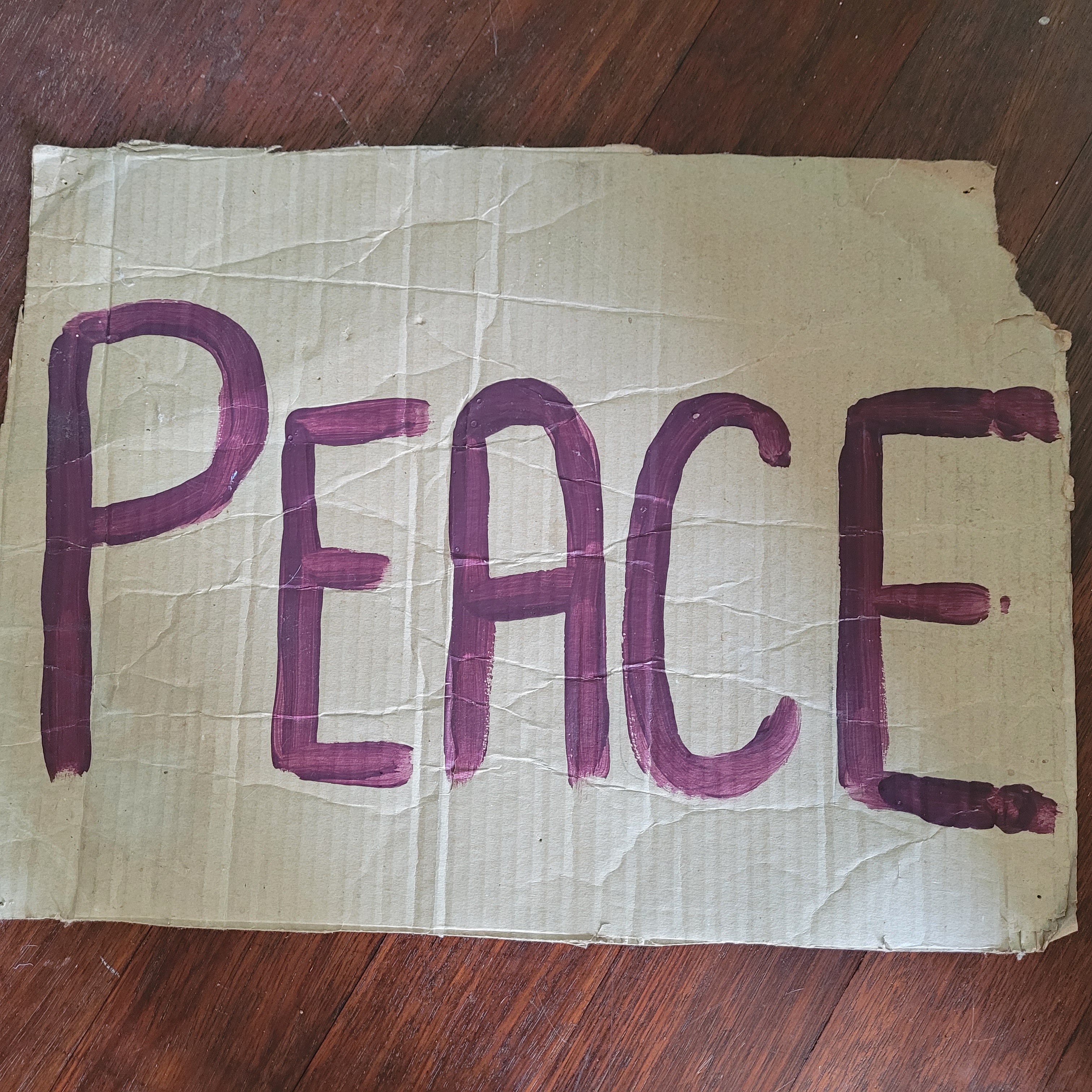

This sign is saved from almost twenty years ago, when my oldest was a baby. The invasion of Iraq was imminent. Three generations of my baby’s family marched: baby, mum and dad, and aunts and grandma on dad’s side. Grandma was nearing the end of her life. She had cancer, and in the middle of an enormous crowd, was frail and vulnerable and confused. And she marched anyway. This was baby’s sign, propped on the pram.

Back in the day, I would protest often. These days, I’ll admit I’m more likely to walk past a protest, on my way from some meeting to another, when I cross Parliament grounds. The grounds are a shortcut, a place where people will stop and chat, or meet for a take-out coffee on the lawn. The coffee drinkers and protesters co-exist. Sometimes you’ll see the anti-abortion folks. They bring a mix of great moral certainty, deck chairs and shitty placards. There was a climate change guy who camped for ages on the lawn, before Wellington’s shite weather presumably defeated him. There are the anti-1080 people, with their camo gear and children.

Protest, of course, is a spectrum. There’s protest, protest with a dash of civil disobedience, protest with serious disruption, and violence. That middle-ish part of the spectrum is tricky: potentially unlawful, but police use discretion in how they respond, and are unlikely to be heavy-handed. Mostly, my youthful protest efforts were at the mild end of the spectrum. I aimed to be no worse than a pain in the arse - an ethic I’ve tried to carry through to adulthood.

The Wellington protesters were a mish-mash of points across the spectrum. To be upfront, my view was that police should exhaust peaceful options first, then use force with restraint. And I have nothing but praise: they’ve handled this with the highest professionalism and skill. But in the last three weeks, police have faced an ethical, as well as literal, shitstorm.

Serious disruption and violence? Easiest. Action is likely to be justified. Civil disobedience? Harder. Most people would agree the civil disobedience we’ve just seen crossed the line - but police have to think about even-handedness. They face the accusation of favouring some political causes over others. And finally, expressing hateful views and peddling conspiracies? Hardest. It’s repugnant. It could incite violence. But the police have to focus on what’s unlawful, not what’s stomach-churning.

These are my kids in 2013, hand in hand, protesting the police’s handling of the Roastbusters case. The older kid had just turned 12. He took a bit of chalk and wrote on the footpath outside the police station, “It’s never the victim’s fault”. That’s right: both freakin apostrophes in the CORRECT PLACES. It was at this point I realised I’m probably the best parent in the world.

Okey dokey. We’re covered the trickiness of judging the moment that protest crosses the line. And that trickiness extends beyond the situation at hand, to the precedent it might create for future protest rights and police responses. But further trickiness awaits us. And this is kōrero we need to have right now.

Our political leaders are weighing up how we stop a thing like this happening again. This includes considering whether protesters should be allowed on Parliament grounds in future. In practice, I’m not sure how this would work. A fence to keep them out? Police to turn them back?

Safety is paramount, so I’m not going to dismiss these ideas out of hand. But I’d question whether they could have prevented the mess we just faced. The problem with the current protest was less that it entered Parliament grounds, and more that it used trucks as a barricade - bringing the surrounding streets to a standstill, and enabling harassment of the people passing through. It’s the tactic that caused the catastrophe, not the particular place the protesters used it. Is Parliament particularly special? In a symbolic sense, of course. In a practical sense, pulling this crap anywhere disruptive will cause human misery. Worrying about Parliament specifically is worrying about the wrong thing.

Short term problems can be fixed by fences and police. Longer term problems demand more reflection. They ask us, how do people - even if their beliefs are despicable - feel so disenfranchised as to set their surrounds on fire? How do conspiracy theories take hold; and how can our culture, our institutions, prevent them? How can a flashpoint situation be diffused in line with police advice, and with some care for the wellbeing of all involved, not become a grasp for social media likes?

Just before Christmas 2019, my big kid - the one with the strong apostrophe game - sent me this photo. He and his friend were baking Christmas cookies, and nothing says Feliz Navidad like a hammer and sickle. The revolution will not be televised, but there’s no reason it shouldn’t have chocolate chips.

The rules we make now will shape our future. They also need to draw on our past.

I said before, I just want to heal. Protest, resistance, holding to my values, standing up when I’m told to sit down - it’s all a part of me. Maybe it’s hard to understand how these things, rooted in conflict, could heal. I will try to explain.

Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi, holding fast as the flames rose and the children cried.

Archibald Baxter, tied up and tortured in the field, relinquishing neither his pacifism nor his courage.

Dame Whina, humility and a headscarf never quite concealing the formidability, the strength of an army.

The ones who stood in Hamilton’s Rugby Park, batons poised to smash their bones and teeth, but still they stood.

There is no moral equivalence here: history won’t be kinder than the present to the ones who threw shit and abused schoolkids. That’s not what I’m saying.

Nine times out of ten - or maybe ninety-nine out of a hundred - protesters will be cranks, irritants, eccentrics. We will step around them on the street, carrying on our conversations. But that other time, rare though it may be, they will hand us our arses as they show us our souls. That’s been our past. And, uncomfortable though it will sometimes be, it has to be our future.