In harm's way

Warning for graphic content.

My grandfather was a police officer. I never really got to know him, and I’m not sure I would’ve liked him if I had. He and my grandmother visited from Scotland when I was a kid - back in the day when long haul flights were as expensive as they were gruelling. I remember he was tall, he made jokes, and he had boiled lollies and fragments of tobacco leaves in his pockets.

He was high ranking, apparently, his police career only slowed by his commitment to his union. I am not surprised by this: he was highly capable, very smart, and if he wasn’t fearless, you couldn’t tell. I never wanted to know the details of his work: policing in mid-century Scotland wasn’t known for its niceties, and snippets I’ve heard are brutal and disturbing. He lived by a code that is foreign to me. He was also deeply principled, though his principles would have differed markedly to mine.

I’ve had a few good experiences with police, and a number of bad ones. I’ve been deeply critical of them many times, and I will be again. But I remember my grandfather, and for all that we would likely disagree, I know this: he would never have flinched from doing his job.

My father was a fireman. This, too, was when I was a kid. Being a fireman was a different job back then: less weight on preventive work, and more on dirt and risk and brute force. He brought stories home - not the worst ones, I don’t think - and they were matter of fact. He always looked pristine in his uniform. I know now that he and his workmates must have showered off the soot and blood and shit and piss before returning home from shifts. They could not shower off the trauma.

From my father, I learned things that must also have been true for my grandfather. I came to understand that the world is unsafe, not in some theoretical sense, but a visceral one. When the fire reaches the ceiling and the panels fall, the skin of children - usually poor children - is burnt from their bodies. People groan or weep as they are cut from glass and metal, in the dark and the rain. Bodies, or parts of them, must be removed from industrial accidents, as gently as you can with a hand knife, before they can be returned to families.

I understood, as a child, there was a chance my father might die at work one day. This didn’t make me feel either particularly anxious or particularly special - I wasn’t different to other emergency workers’ kids. But I did not assume physical safety. Its absence was the baseline from which I measured my world. It still is.

This mindset this leads to is odd, maybe, and hard to explain. I can’t say if it’s the same for other whānau of emergency workers, but I grew up with the belief that if you see a situation, and you can intervene safely, that’s what you’ve got to do. I can’t offer you any tales of heroism, or even competence. I doubt I’ve ever been in any real danger: the worst I’ve had is being told to fuck off. But each time it’s happened - conflict imminent or actual - I’ve felt the same way. My heart thuds until I feel nauseous. There is fear in my voice, and I try to clench it in, so it will not disintegrate into tears. Adrenalin lasts for a shaky hour after.

The thing I am describing, and you may know it too, is the body’s reaction to the fear of harm. My examples are trivial. But after each time, I’ve reflected on where I come from, asking whether I would - whether I could - put myself in harm’s way for another person. Every time, regardless what I want it to be, my answer to myself is the same.

We are debating right now how police are handling the protesters in Wellington. We are asking whether they’re prepared, able, ethical. These are all fair questions, important in a democracy. But we ask them, almost all of us, from a baseline of physical safety. We have theoretical answers to a visceral reality. It’s just a few tents and trucks and malcontents. How hard can it be?

Some people, because it’s their job, have to put themselves in harm’s way, and that doesn’t feel like other jobs feel. We don’t have to reserve our judgement, but we do need to extend our imaginations, beyond our own baselines. We need to understand, really understand, what it means to go to work and be unsafe. If the people who are willing to do that have concerns - about safety, or tactics, or anything else within their expertise - I’m personally willing to hear them out. Maybe they’re not simply unwilling to do their jobs, or whatever is the wisdom of Twitter. Maybe they know stuff we don’t.

If he was alive today, I wonder what kind of conversation I’d have with my grandfather. He’d be bemused by my weird mix of insubordination and hippy nonsense. I think I would feel both pride and dismay. I don’t know, to be honest, if we’d be able to bridge that gap: to find sympathy or common ground between us.

But I know, if he were here, he wouldn’t flinch from doing his job.

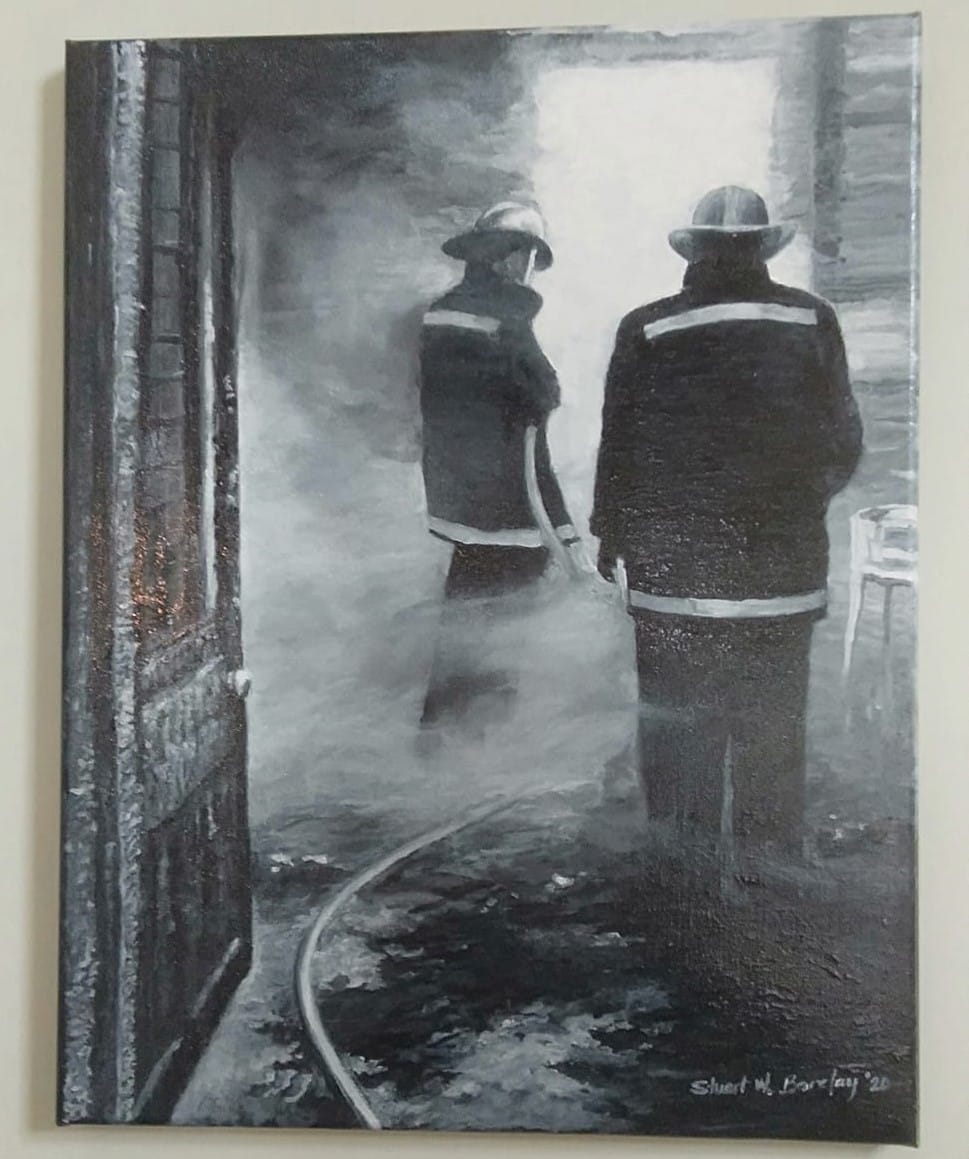

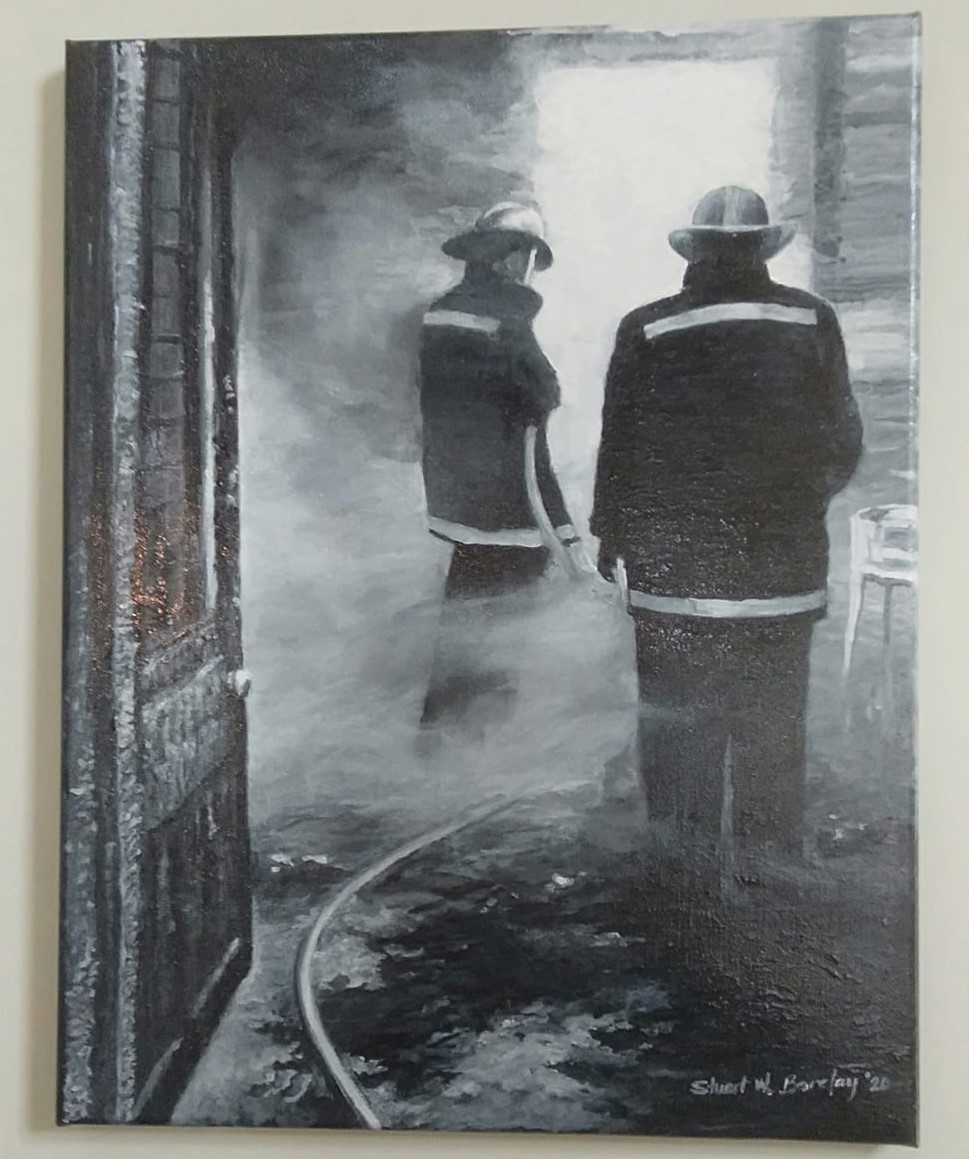

This painting is by one Stu Barclay, an ex-fireman who served with my father. The painting was reproduced from a Southland Times article in the 80s, and features my father and his colleague. The fire was extremely serious - hence the newspaper coverage - although I’m unsure whether it was a fatality. The lack of breathing apparatus shows the photo was taken at the point of clean up after the fire.