Nerd Monday: Tearing up the rule book?

A word of warning. Regulation is a super complex area with a bunch of experts, and I'm definitely not one of them. But I've been reading and discovering some ideas. Hold on to your hat!

The guy intercepted me on Castle Street, Dunedin, catching me up from behind as I headed south, trudging in my green woolly jersey and my Doc Martens. We walked together, past the weatherboard flats with the dilapidated couches out front.

We were both students. He was a friend of a friend - and I have a feeling they’d met in an ecology class or similar, both of them drawn to Papatūānuku with that reverence, that pleasure, that is gifted to some. Maybe he was an extrovert, or at least in comparison to me. I liked him anyway. We chatted as we walked; or, perhaps, he chatted and I listened.

It was 1994, and my first year at university. I was getting political, wrestling a little clumsily with new words and ideas. And there was plenty to wrestle with: my mates and I had come of age in a moment of turmoil for Aotearoa, social and political and economic. If that wasn’t enough, I also had to figure out what to study each semester, get my head around the lecture schedule, get out of bed on time, cook for my flatmates on Thursdays.

On Castle Street, the sash windows of the flats were pushed up. People played Cranberries and Counting Crows CDs from inside, drunk cheap beers on the porch. Probably, we kept half an eye on the footpath as we walked, circumventing rubbish or glass. He and I went our ways at the campus gates.

I wouldn’t have remembered any of this, except these would prove to be the last months of Abram’s life.

This piece is about regulation. Regulation is a hot topic right now, as we head into the election. ACT is proposing a Ministry of Regulation, to clean up “the jungle of red tape that holds New Zealand back”. ACT leader David Seymour talks about over-the-top regulations he wants to cull, like rules around the application of nappy cream.

These concerns aren’t new. Seymour’s tapping into something here: a political current, in Aotearoa and elsewhere, that resists rules made by governments - and even questions the legitimacy of government’s role as rule maker.

First, what is regulation? In the literal sense, regulation is a form of law. Folks like Seymour tend to be concerned mostly with regulations on business, because meeting these regulations (compliance) tends to create business costs. This in turn affects productivity, and the bigger economy. However, folks like Seymour will sometimes use the concept of regulation to mean any instance - real or perceived - of the government telling people what to do. This is more of a philosophical debate, and we’ll come back to it.

Maybe you’re thinking to yourself, “Why should I care about the rules around nappy cream? These days, my skin hardly needs it.”

Well, regulation is a big deal. It has important aims, like keeping people safe, making sure they’re treated fairly, looking after the environment, and helping the economy do well. Getting the right amount of regulation matters. But to my mind, regulating the right things, and making sure it’s good quality regulation, matter more. To make the case, let’s start with a tiki tour through our history.

Once upon a time, there was a small country at the bottom of the Pacific. Let’s call this country ‘Aotearoa’. It’s got a nicer ring than some randomly chosen Dutch name.

Like plenty of other countries, Aotearoa went through some tough times in the twentieth century. There was a world war, a great depression, and another world war. And as in other countries, these events created a great deal of misery, chaos, deprivation and inequality. Aotearoa came through those experiences with a conviction we needed to do economy and society a bit differently.

From the 1930s onwards, our government set in place a bunch of policies called ‘protectionism’. In short, protectionism was a system of regulations to keep the economy going well - mostly by sheltering it from competition. Regulations prevented people and businesses from doing a bunch of stuff, or forced them to do a bunch of stuff, but they also had upsides, like keeping employment high. (At the same time, kiwis’ lives were regulated in other ways that weren’t so much economic. For example, it was illegal for gay men to have sex, and unwed mothers weren’t entitled to benefits like other women with children.) During most of this protectionist era, Aotearoa was pretty wealthy by international standards.

Protectionism worked until it didn’t. Especially from the late 1970s, Aotearoa’s economy shat the bed, and our go-to policies would no longer fix it. But before we get to that part of our tale, let me offer you a couple of stories from my mum, to illustrate how protectionism worked.

Back in the day, my mum’s family - both sides - came from a small place in Southland called Winton. Winton is a farming town, and farmers need to get their stuff to market. In the mid-twentieth century, Aotearoa had a bitchin’ railway network, owned by the government. And a bunch of people worked for the railways, helping maintain high employment. The government wanted to protect the railways. (Note: my point isn’t to say whether that was a good goal or not. We’re simply looking at how the government tried to achieve it.)

From the 1960s onwards, vehicle ownership became more common. Now farmers had a choice: they could use trains to freight their stuff, or they could hire trucks. But if they hired trucks, that would be no good for the government-owned railways. How did the government respond? Trucks were regulated. If you wanted to be a commercial truck driver, you had to apply for a license, and you could only freight stuff a certain distance. This effectively forced farmers and others to keep using the trains.

The legend goes that my great great grandfather, Patrick O’Shannessy, wanted to take a racehorse from Winton to Lawrence, a town in South Otago. The horse got trucked to East Lime Hills (near Winton), sent by train to Invercargill (further south), back up to Milton (South Otago), then inland to Lawrence. This turned a 154km trip into a 225km trip.

If I was the horse I would have been ANNOYED.

Photo caption: The other side of my mum’s family - we’ll come to them in a minute - actually owned a commercial truck. They had to apply for a government licence to operate. Today, the truck lives in a museum in Invercargill, and it’s so SHINY. I’m glad my grandfather never lived to see my lichen-and-shame-encrusted Prius.

The horse is the first family story. Here’s the second story, this time from World War Two, and it doesn’t show my forebears in the best light.

With all the disruptions of the war, getting stuff to market could be extra tricky. Winton farmers had to put their stuff on the trains - but there weren’t always enough rail wagons. Wagons were allocated across the farmers using a system: farmers’ names were scrawled on the sides of the wagons with chalk. The O’Shannessys and Murphys (the other side of my family) collaborated on a plan, simply hanging out at the railway station, chalk in their pockets, and scrawling ‘O’Shannessy’ on any spare wagons. The community never figured out how, when everyone else struggled for wagon space, the O’Shannessys always seemed to do just fine.

OK, what have we covered in this section? Regulation can have admirable goals. Sometimes it has met those goals, and sometimes it hasn’t. Badly designed regulation might not just fail to meet its goals: it might even mess with people or businesses in an unreasonable way. And there are some people and businesses who will look for the weak spots in any regulation, seeing if they can use them for advantage.

We’ve had a sneak peek at regulation in its heyday. What happened next?

In the 1980s and 1990s, neoliberalism happened. (I hate the word neoliberalism, because it lacks a clear definition, but let’s stick with it for now.)

There are lots of accounts, but for our kōrero, what matters is that neoliberalism told government intervention to get back in its box. Neoliberalism said, the economy should be left in private hands to do its own thing, without the government controlling a chunk of it. Markets should run themselves, without government trying to smooth their hard edges. People shouldn’t have their choice removed by being taxed, then having that tax spent on government services they might not even want to use. Personal freedom ruled. And if people used their personal freedom to make bad choices, ending up poor or sick or marginalised - well, that was on them. It wasn’t government’s job to dry every tear.

This is when people started talking about the ‘nanny state’, a weirdly gendered term you still hear today to describe a government that makes regulations. If the nanny state was a nagging joyless woman who told you what you could and couldn’t do, neoliberalism was more like your cool dad. Cool dad doesn’t tell you not to jump off the roof with your mates - that’s PC gone mad! That said, cool dad’s not going to take you to ED with your broken leg. You’ve got two legs: just hop there on the other one. It’s called personal responsibility, cool dad says, when you stay at his house every second weekend.

That metaphor went too far, but you get the gist: parts of our political culture, even our society, developed almost an hostility towards regulation - and not just specific examples of bad regulation, but the whole idea of regulation, full stop. Freedom good, rules bad. This was happening all around the world, but Aotearoa brought our own nationalist streak to our regulation conversation - one that David Seymour is tapping into now. In our land of number 8 wire and practicality, we didn’t need these Wellington ivory tower plonkers telling us what to do from their offices. Governments of the 1980s and 1990s let loose with a programme of deregulation, or a dismantling of rules - and its fallout was still very real that day Abram and I walked down Castle Street together.

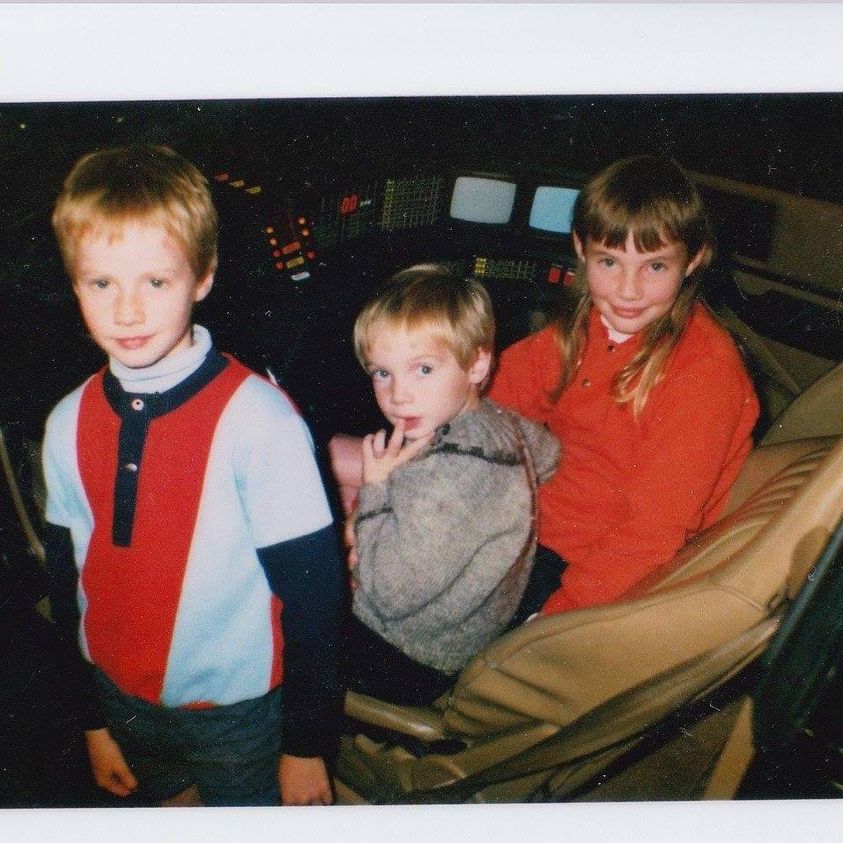

Photo caption: This is a picture of me and two of my brothers in KITT from Knight Rider, which came to Aotearoa in the 1980s. You can tell deregulation has gone too far, because how else could that mullet I’m sporting be legal?

Allow me to get technical on yo ass for a short moment. Treasury was one of the movers and shakers behind the neoliberal reforms. Looking at their ideas of the time gives us a window into why some folks had strong feelings about deregulation:

- Governments should make rules for the basic stuff, like upholding property rights and making sure people honour any contracts they enter into. Beyond that, the government should ask: can people and businesses sort this problem out for themselves? Regulation may not be needed.

- Even when there’s a problem the government genuinely needs to fix, it shouldn’t default to regulation. There might be other ways to achieve government aims.

- When you put rules in place, people and businesses spend time and money figuring out how to get around those rules. Instead, they could be doing something more economically productive.

- Some businesses or industries actually want regulation, because it can help them keep competitors out. Suddenly these guys are coining it, because the government gave them an unfair advantage. That should be a no-no.

- Regulation raises prices for everyday folks like you and me. The more rules a business has to meet, the more it costs them, and the more those costs get passed onto us.

- Regulation can have flow-on impacts for other areas. For example, if people keep getting free hospital care, they might slack off their exercise and diet. (I know, this one makes no sense at all. Don’t shoot the messenger.)

- Just because the market is doing a shit job of something doesn’t mean the government will be any better.

You can see not all these ideas are wackadoodle - but they’re pretty broad brush. Think about all the things in your life that are regulated, from your GP to your tattooist to your electrician, the quality of the water flowing from your kitchen tap, the bank that holds your money, the hygiene standards at your local café, even the welfare of your pets. Is it possible to wave a magic wand - freedom good, rules bad - and come up with an approach that solves all the different issues in all these different areas?

Real life is kind of tricky. Let’s move on to another story that proves the point.

This case study comes from the fabulous work of Peter Mumford, a kiwi regulation expert. Any shortcomings in the retelling are entirely mine.

Back in the day, house-building in Aotearoa was pretty old school. There were rules about how stuff had to be done, and those rules were specific. Building standards even set out the methods builders had to use.

People thought the building industry was over-regulated - and, to be fair, it wasn’t perfect. This old school way of regulating, telling people how to do stuff, has its plusses: reliable quality. But following all those rules comes at a cost, making things more expensive. And it’s inflexible. Got a bright idea for doing things better, more efficiently? You’re probably shit out of luck: the law may give you little room to move.

In 1991, the government ushered in a whole new approach: something called a performance-based building control regime. What’s that? Well, instead of telling people how to do stuff, these new regulations only told them what they had to do - what ‘performance’ standards to meet. In short, the government said, ‘Building industry, your job is to make sure houses are weathertight. You guys figure out the how. You don’t need us to tell you’. Instead of following a bunch of specific rules, the industry now had to make more judgements about what was up to scratch.

And what happened next? It’s like there was a chain, but every link was weak.

With the old rules gone, there was more room to try new stuff. Fancy schmancy building designs were getting popular - involving something called monolithic cladding. Territorial authorities (part of local government) had the job of approving the new designs, but it was a hard job to get right because the designs were novel.

So far, so tricky: but it got a whole lot trickier. That monolithic cladding? It didn’t allow a space between the cladding itself and the wall of the house. Inside the wall were wooden joints, but they were made from new stuff called ‘kiln-dried timber’, not old school treated timber. To add to the problem, another trend began: building houses without eaves. (This allowed bigger houses, because houses could be built closer to the edges of sections.)

Aotearoa now faced a perfect storm. Our literal storms - rain driven sideways by the wind - got onto the monolithic cladding, more than they should have, because there were no eaves for protection. The monolithic cladding wasn’t watertight enough for our conditions. Because there was no space between cladding and wall, water then got into the joints. The timber wasn’t treated, so the joints rotted. People’s homes, their lives, everything they had, were quite literally disintegrating around them.

This was a system with many moving parts: but no one from the government was watching over the whole. Nobody picked up the signs. If they had, and if they’d acted on them, perhaps the ruin could have been confined to hundreds of homes. Instead, it ran to the thousands.

This, of course, was Aotearoa’s leaky homes crisis. It’s known as one of our country’s most catastrophic regulatory failures. The most recent estimates I can find put it at 89,000 homes and a cost of $50 billion. That doesn’t include people who haven’t yet discovered their homes are rotting, their properties worth a fraction of their purchase price, their retirement plans shot. The human cost is harder to say. In 2007, the Herald reported bankruptcy, ill health, anxiety and depression; people hounded by their body corporate for eyewatering repair costs they simply couldn’t pay. There was one known suicide, and many other people said to be on ‘suicide watch’. I can’t find more up-to-date stories about how these people are faring. Sometimes the price is too painful to count.

OK. We’ve seen how regulation, done poorly, can be catastrophic; and we’ve seen the harm when this happens. What does regulation look like when it goes right?

These days, the law says government has to do a good job of regulation. Treasury (along with others) still has the task of telling the rest of government what good regulation looks like. Its advice has changed over the years as it’s become less ideological, and as the evidence around regulation has developed. So, what does Treasury have to say? Here’s my potted version.

For a start, regulations should only be made when they’re needed. If they’re needed, they should:

- be clear what they’re trying to achieve

- try not to create costs, or mess with markets, property rights or individuals

- be flexible to meet different people’s needs, move with the times, and allow for bright new ideas

- be predictable, so people aren’t getting mucked around

- be proportionate - not using a sledgehammer to crack a nut - and fair to different people

- support Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations

- be easy to understand and comply with

To my untrained eye, these standards seem pretty sensible, more or less. Are we good? Is there no problem left to fix?

We might have a clear idea what good looks like, but that’s not to say all regulations meet these standards: politicians, bless them, have a way of saying one thing and doing another. Taking a step back, there have been calls to think about our whole system for regulation in Aotearoa - not just the rules themselves, but how well the government carries them out. In 2014, the Productivity Commission found Aotearoa has room for improvement: regulations not moving with the times, no one keeping an eye on regulators themselves, and regulators having weak leadership and poor cultures.

Added to that, we have to stay on our toes: a changing world requires changing rules. Jeroen van der Heijden, another expert, reckons regulators face ‘insidious challenges’ in the twenty-first century - and not just technology, climate change and the pandemic. Some past regulatory reforms need to be redone, which is hard. In fact, some need to be redesigned from scratch, but that’s like building the plane when you’re flying it. It’s getting hard to design rules that work for everyone in an increasingly diverse society. And - it’s this one that gets me - people don’t always see the point of regulation anymore.

These are big issues, fascinating issues, and above my head. But it’s clear that work is needed. I'm just not sure it’s got much to do with nappy cream.

Ultimately, it was the nails. Bolts should have been used. The nails simply sheered away from their moorings, under the weight of the people.

But it wasn’t just the nails. The builders, well-intentioned volunteers who hammered the nails in, didn’t know what they were doing. They had no framework to guide them, tell them how to proceed. No one managed them or the process. There should have been an engineer behind the planning, but there wasn’t. Nor was there enough funding. The law wasn’t being met, but no one inspected the build, so no one picked it up.

Everyone involved was trying to meet public demand for the platform. Whatever the Department of Conservation thought the public was demanding, well, I guess it wasn’t red tape, bureaucratic hold-ups, more rules. What it added up to, every small moment of negligence, every corner cut, was another of Aotearoa’s most catastrophic regulatory failures - the subject of articles even today.

And that was how Abram died. He was one of fourteen, most of them not much more than kids. When the platform collapsed, nails sheering off their moorings, they fell forty metres. They died together, the fourteen of them, on 28 April 1995, on the rocks of Cave Creek.

They died for want of a handful of bolts instead of nails; for want of a political system that distinguished between one and the other, that gave a f*** about the catastrophic difference.

Freedom good, rules bad. We all followed the recovery of the bodies on the news.

That’s what I think about, when we talk about regulation. We can cast it as the work of a nanny state, imposing on our rights; get our hackles up and shake our fists. Or we could, as citizens, get smarter and more ethical; debate the nuance, balance carefully all the issues and interests at play. We could - and this bleeding-heart notion will baffle some - think about regulation as our considered expression of care, for ourselves, for others, for our planet.

This stuff can’t be left to slogans. In this twenty-first century, we need to get it right. We have to get it right. The stakes are just too high if we don’t.

The End is Naenae is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.