Nerd Sunday: School's out

Our kids don't go to school anymore. We need to talk about the evidence, but with compassion. I'll do my darndest to weave these two things together in this post.

Maybe it’s weird I became a battleaxe mum, at least when it comes to school attendance. My kids have always gone to school. They got one day off for a family wedding sometime in the 2010s, but outside of that, the only excuse has been sickness. You get up, kiddo, and off you go. Am I being smug?

If I am being smug, it’s not intentional. If anything, I would say I’m replicating values I grew up with, that a bunch of us did. Let’s unpack this further. I think it helps make sense of what will follow.

I went to school when I didn’t feel like it. I went to school when I was sick. I went to school when the pissing Southland rain soaked through my coat, and I had to sit in soggy clothes all day. I went to school when I was bullied. I went to school on what we then called mufti day, although I had no nice clothes, and I knew I’d be bullied some more. I went to school when I was exhausted, because my chronic anxiety caused terrible insomnia - and I barely bothered mentioning it to the adults around me, because I know I’d just be told to go to school.

Some of you are reading this and it’s striking a chord. It’s not a dig at anybody. Back in the day, this attitude to school wasn’t even uncommon. When I wonder why, I suspect it’s partly because our mothers, more of whom stayed at home with us, wanted us out from under their feet. Fair enough. But it was also something more.

I’m Gen X. I was the first in my family to go to university. That wasn’t an accident: school represented something to working class families like mine, our baby boomer parents, many of whom had dismal school experiences themselves. It represented social mobility, when Aotearoa still cared about that sort of thing; and the idea that if you worked hard, you could build something for your kids. They in turn would build something a little more for theirs.

Am I glad I got sent to school, come hell or high water? It’s a hard question to answer. I think if I’d had the choice to give up - especially in the face of my mental health stuff - I might just have taken it. The life I have today might have been lost to me, before I could even have imagined it. On the other hand, I was so often desperately unhappy. And when I became a mum, I didn’t want to be the kind who doesn’t listen to her kids’ school struggles - or whose kids won’t confide in her at all. I’ve always walked a line around this stuff; or if I’m honest, stumbled around that line, doubting myself, feeling guilty.

These are hard issues to talk about. Let’s do it anyway. I’ve been rummaging around the research, to create an explainer on why kids don’t go to school. If you make it to the end, I promise you’ll get full marks for attendance.

Let’s take it from the top. Why does school attendance matter?

I hear you saying, if kids don’t go to school, they can’t learn. DUH. You’re right, of course, but there’s a little more to the story. Let’s have a look.

We’ll start with the link between attendance and attainment (getting qualifications). That link is really close. Simply put, the more a kid attends, the better they do, and even a few days missed can make the difference. The only ‘safe’ level of non-attendance, before it starts impacting a kid’s attainment, is 1.5 days of justified absence in a term (we’ll come back to justified and unjustified absences). The first few unjustified days off in a term are associated with the biggest drop-off in a kid’s attainment.1

What about the relationship between attendance and wellbeing? Well, this isn’t straightforward. As we’re going to see, school is a mixed experience for some kids. But Ministry of Education research from 2020 (based on 2015 data that kids self-reported) made these findings, quoted directly:

Skipping a greater number of school days over the preceding fortnight predicts worse average wellbeing outcomes.

Skipping no days of school over the preceding fortnight is predictive of the best average outcomes for wellbeing.2

Kids who don’t go to school are at greater risk of a bunch of negative stuff, from dropping out and being isolated to poor mental health and even crime.3 In short, going to school is a good idea.

Yes, OK, school attendance matters. But just how bad is our attendance problem?

It’s bad. Look.

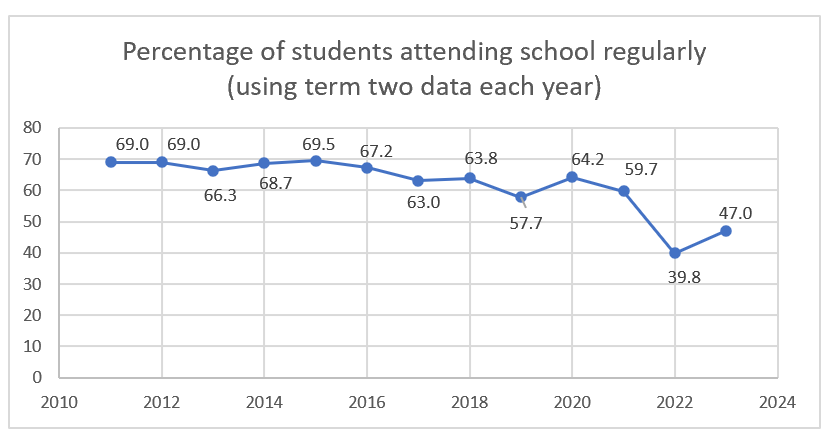

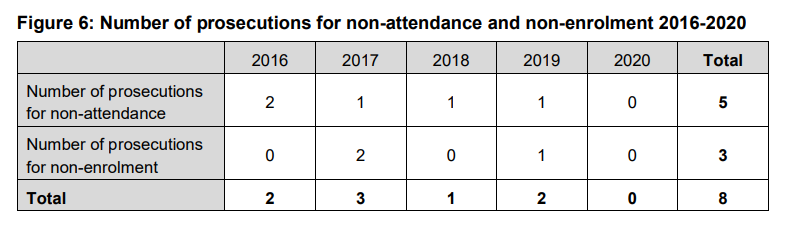

I made this graph MYSELF using Ministry of Education data. I don’t expect a pat on the back - but if you wanted to give me one, you know where to find me.

This data shows the percentage of kids attending school regularly in term two of each year.4 You’ll see that regular attendance was mostly around 69% until 2015, when it started to track downwards. Last year was a shitter, hitting 39.8%, before we rebounded to a still-pretty-bad 47%. It’s too soon to know whether the rebound will continue. Within these stats, a whole lot of inequality is lurking: the downward trend has been sharper for Māori kids, Pacific kids, and kids from low decile schools. But that’s not an invitation to finger-point. This trend has been happening to all kids, right across the board.5

You’re probably asking, doesn’t COVID account for a lot of this? It’s a good question, and the answer is ‘kind of’.

Consistent with the downturn since 2015, attendance was set to drop again in early 2020, when the pandemic hit. Then, with COVID arriving, attendance actually went up - especially after we came out of level 3.6 Of course, that wasn’t the end of the story. In term two last year, when regular attendance hit a dire 39.8%, COVID was being a right dick - so a whole lot of kids were staying away sick, or because they were following the self-isolation rules. But not all. Other kids were just … checking out.7 Towards the end of 2021, the Ministry of Education observed that, of the kids whose attendance reduced with COVID, 40% had had no problems beforehand.8

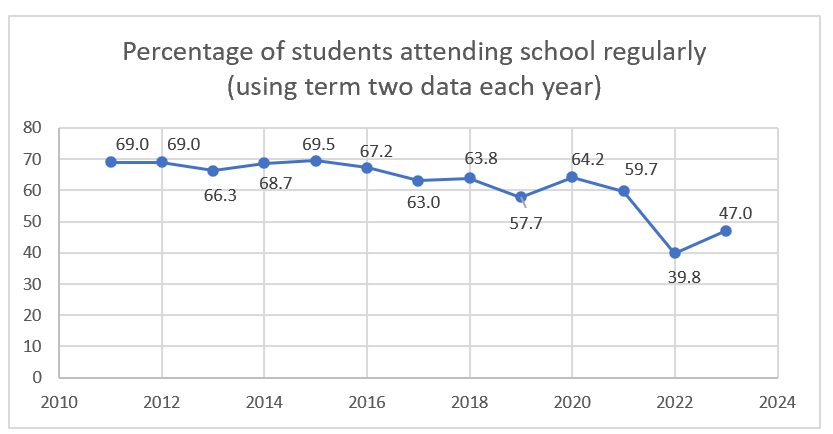

It’s fair to ask at this point, is Aotearoa better or worse than anyone else - seeing as attendance is dropping all over the show? Sorry. By international standards, unfortunately, we’re not flash either.

This data is a little bit muddly, because different countries measure attendance in slightly different ways, and different years are being compared. But you get the gist. This isn’t our best work.9

So yeah, our attendance problem is bad. But how did we get here? To answer that, we first need to cover the rules for attendance, and how attendance is measured. Bear with me, nerdz.

What are the rules for school attendance?

My first discovery, and it was kind of surprising, is the rules for attendance aren’t that easy to figure out. I started reading the Education and Training Act 2020, and got a certain way through before becoming bored and deciding I’d wait for the movie.10 Still, the Act confirmed some basic stuff for me:

Kids aged between 6 and 16 years have to be enrolled at school. And they have to attend school, if school’s open. That includes enrolled 5-year-olds (contrary to some people’s beliefs).

Kids who have wellbeing needs, or who need a ‘transitional plan’ to ease into school, can sometimes go part-time - but getting permission for a kid to go part-time is hard.11 Kids’ wellbeing is tricky and contentious, and we’ll touch on it later.

There are some other situations where kids can be exempt from attending, or can leave school before age 16, but these are pretty specific, like being in a secondary-tertiary programme.

Schools have a legal responsibility to do their best to make sure kids attend.

Parents who don’t make sure their kids attend school are committing an offence and can be fined. We’ll come back to this too.

That’s the big picture. Now it’s time for the details.

So you skipped maths class? I’ll try to explain the data.

When it comes to the day-to-day, what really matters is justified versus unjustified absences. If you’re a parent who’s ever got that awkward phone call from school at morning teatime, you know what I’m talking about.

A justified absence means sickness or medical reasons, other reasons that fall within a school’s attendance policy, or being stood down or suspended. An unjustified absence is, well, anything that isn’t justified. It’s essentially giving no reason for a kid’s absence, giving a reason that’s not good enough, or going on holiday during term time.12

The Ministry of Education asks schools to record kids’ attendance, both morning and afternoon, using a bunch of codes that represent different reasons for absence.13 The Ministry hoovers up schools’ data and figures out the percentage of kids who have:

Regular attendance (more than 90% of the time)

Irregular absence (attending more than 80%, and up to 90%)

Moderate absence (attending more than 70%, and up to 80%)

Chronic absence (attending 70% or less)14

The Ministry then compiles a series of colourful graphs that make us feel stink as an entire nation.

We’ve done the nerdy bits. Let’s return to that all-important question: how did we get here?

This was another surprise: kiwi evidence on why kids don’t go to school wasn’t as easy to find as you’d think. The best I could unearth was a 2022 project by the Education Review Office (ERO), looking at the views of kids, parents and schools on school attendance (English medium schools only). The parents and kids were representative of the whole population - not families singled out for having attendance problems.

Let’s draw on the ERO report, remembering that people’s views on attendance won’t always be the same as their actual behaviour.

Before we start, I want to acknowledge this stuff can make people judgy. Racist-judgy. Classist-judgy. Self-judgy, if you’re like me, and you spy a reason on the list you'd let your own kid miss school; and now you’re furtively trying to calculate just how shitty a parent you are, relative to the rest. Without suggesting anything goes - we have a problem, Aotearoa - I’m going to invite you to park any judgement. Let’s work on understanding first.

A lot of parents and kids didn’t see the importance of going to school.

- 41% of parents were comfortable with their kid missing a week or more of school in a term.

- Parents thought regular attendance was less important in primary than secondary school.

- 33% of kids didn’t think going to school every day is important.

- 22% of kids didn’t think school is that important for their futures.

A lot of parents prioritised other things ahead of school.

- 67% of parents said they’d likely keep their children home for a family, cultural, or special event (this was more important to Māori and Pacific parents).

- 41% said they’d likely take their kid out of school to participate in a sports event. (Note, the report also found some parents were taking their kids out of school for cultural activities, like drama or dancing.)

- 35% said they’d likely take their kid out of school for a holiday of a week or more.

- 12% said they’d likely keep their kid home on the kid’s birthday.

- 7% said they’d likely keep their kid out of school to look after another family member.

- 7% said they’d likely keep their kid out of school to do paid work.

A lot of kids prioritised other things ahead of school too.

- 33% of kids said they want to miss school because they have more enjoyable things to do.

- 17% said they want to miss school because they have whānau, cultural, or special events during school time.

- 8% said they want to miss school because they have responsibilities to look after other family members.

- Fascinatingly, there was a socioeconomic difference in kids’ motivation to go to school, and it’s the opposite way you’d expect, with the low decile kids being more motivated. High decile kids were more likely to want to miss school because they had more enjoyable things to do (40% of high decile kids, 22% of low decile kids), because they don’t like getting up in the morning when they’re tired (38% of high decile kids, 27% of low decile kids), if they don’t like or aren’t interested in what’s being taught (26% of high decile kids, 9% of low decile kids), or if they don’t like at least one of their teachers (22% of high decile kids, 8% percent of low decile kids).

Kids (and their parents) face a bunch of barriers to school attendance.

The ERO report gathered people’s views on barriers to kids attending school. Let’s quickly rip through them.

- Physical health (including Covid-19 and related anxieties). 67% of parents said they were likely to keep their kid home with a minor illness or injury. Remember, this research was done in 2022, when COVID was being a dick, so this makes sense: parents were feeling more cautious than usual. Kids also identified COVID as something they were worried about, and a reason they’d missed school previously.

- Mental health. 46% of parents said they were likely to keep their kid out of school for mental health reasons. Kids also identified anxiety and other mental health challenges as barriers, and schools noted an upswing in mental health as a reason for absence. Remember: Aotearoa does have high rates of poor mental wellbeing in kids, as well as intolerable youth suicide rates.

- Bullying and other friend-related issues. 38% of parents said they were likely to keep their kid home from school because of bullying. 10% of kids said bullying made them want to miss school. 15% said not liking kids in their class made them want to miss school. Bullying, like youth mental health, is another area Aotearoa does a rubbish job.

- Certain school activities. 18% of parents said they were likely to keep their kid home from school if the kid couldn’t participate in school activities or events. 21% of kids didn’t want to go to school if there was a school activity they wanted to avoid (just typing that brought back memories of frickin cross-country day).

- Lack of engagement with school. 7% of parents said they would likely keep their kid home from school if the kid didn’t want to go. Kids themselves gave reasons for their lack of engagement: not liking or being interested in what’s being taught, not liking teachers, finding schoolwork either too hard or too easy, or not seeing school as relevant to their futures.

- Lack of sleep. 12% of parents said they were likely to keep a tired kid home. 35% of kids didn’t want to go to school if they woke up tired after being up late. Being up late was often due to activities, but could also be gaming.

- Transport. 10% of parents were likely to keep a kid home because of transport challenges.

- Hardship. 13% of parents said they were likely to keep their kid home if they didn’t have the stuff they needed for school (for example, shoes, uniform, money for events).

Barriers to attendance aren’t equal opportunity - and some kids are way worse off than others.

Back to the equity question. The ERO report shows that Māori kids, Pacific kids, and kids from low decile schools have worse attendance outcomes than other kids (although they experience positive factors too, like low decile kids being more motivated to go to school). There are also differences between rural and urban kids, younger and older kids. But where I want to focus, because it’s a simple disgrace, is disabled kids.

Disabled kids were more likely to want to miss school because:

- They can’t participate in some activities at school (14% of disabled kids, 3% of non-disabled kids).

- They don’t want to participate in certain activities at school (31% of disabled kids, 20% of non-disabled kids)

- Their schoolwork is too hard (27% of disabled kids, 11% of non-disabled kids).

Parents of disabled kids reported their kid had missed school over the last term at much higher rates than other kids, because they had a chronic illness (19% of parents of disabled kids, 10% of parents of non-disabled children), or because they had anxiety or other mental health challenges (35% of parents of disabled kids, 7% of parents of non-disabled kids).

Disabled kids were less likely to be motivated to go to school, because they don’t get the chance to do activities like sports or clubs. They were more likely to lack stuff they needed to go to school (19% of disabled kids, 11% of non-disable kids). They were more likely to miss school because they’re bullied (20% of disabled learners, 8% of non-disabled kids). Perhaps inevitably, given all that, disabled kids were less likely to think school was important, or even that their school cared about them.

There are a couple of things to note about the ERO report. The first is that it groups reasons for not attending schools as either ‘different priorities’ or ‘actual barriers’. This isn’t necessarily how I’d categorise the reasons: I think it implies families have more choices than some actually do.

Second, the ERO report doesn’t set out to delve into the ‘reasons behind the reasons’ kids don’t go to school. Why are some of our kids experiencing racism - and what’s being done about it? What about bullying? What exactly is happening with kids’ mental health? And why in 2023 aren’t disabled kids getting a fair go? These are all massive questions - and while they’re too big to tackle now, I want to acknowledge that they matter.

What happens to kids who don’t attend?

OK. We’ve seen why kids aren’t attending school - or at least the high-level picture, if not the underlying causes. What happens when non-attendance gets really bad?

First, of course, the school does its best to get the kid turning up. And some schools are bloody amazing. In Northland, for example, 150 schools banded together, working with the Ministry of Education, to come up with Let's Get to School Tai Tokerau. Families in the area had a lot going on, with some living in garages or caravans, some struggling for food and petrol, and some believing rumours that schools would forcibly vaccinate their kids. Using incentives, like brownie points and grocery vouchers, and creating an engaging curriculum, involving fun stuff like a Master Chef competition, the initiative got a torrent of kids back through the door, with some classrooms hitting 100% attendance.15

But schools can’t fix everything, or sometimes don’t want to (as we’ll see in a minute). That’s when they might refer to the Attendance Service - a network of national providers contracted by the Ministry of Education.16 Now, the Attendance Service has come in for its share of criticism, but it’s worth pausing a moment to understand how hard their jobs are - and the challenges facing the families they work with. This Stuff article from 2017, about an Attendance Service provider called Te Ora Hou and the kids it works with, offers some insight.17

There’s Daniel, then aged 12. With his autism and ADHD, no school would enrol him for weeks. He often slept only a couple of hours a night - meaning that was all the sleep his mum got too. She begged for help from social services to no avail, until Te Ora Hou took the family on.

There’s Phoenix, then aged 10. Phoenix wouldn’t sleep; had been afraid to since the Christchurch earthquakes. He’d even whack himself in the head to stay awake, once doing a stint of 36 hours without sleeping. Although he was 10, he was the size of a much bigger kid, and his mum and his gran simply couldn’t move him. Finding the right school, and therapy to help with his sleep, got Phoenix through.

There’s James, then aged 13, but his anxiety had been debilitating since he was 9. That anxiety would sometimes turn to violence. Past schools had given up on him. At first, Te Ora Hou worked to engage him in conversation, to understand what was happening for him. Then they’d drive James around the school - not yet going inside, but inching closer and closer. After a time, James became able to enter the school buildings.

Then there’s Reuben who, then aged 16, was older than most. His barrier was a mix of family problems and no self-confidence. He took some winning over. Working with Reuben took time, conversation, a few burgers. After a while, Reuben had the realisation that he just needed to be more confident, and he’d reach his potential. He went back to school.

I think it’s Reuben who gets the last word here: "A lot goes on in other people's lives. You can't judge someone just by their attendance or something. They might be going through a tough time."

When all else fails, it’s time to prosecute the crap out of parents. Right?

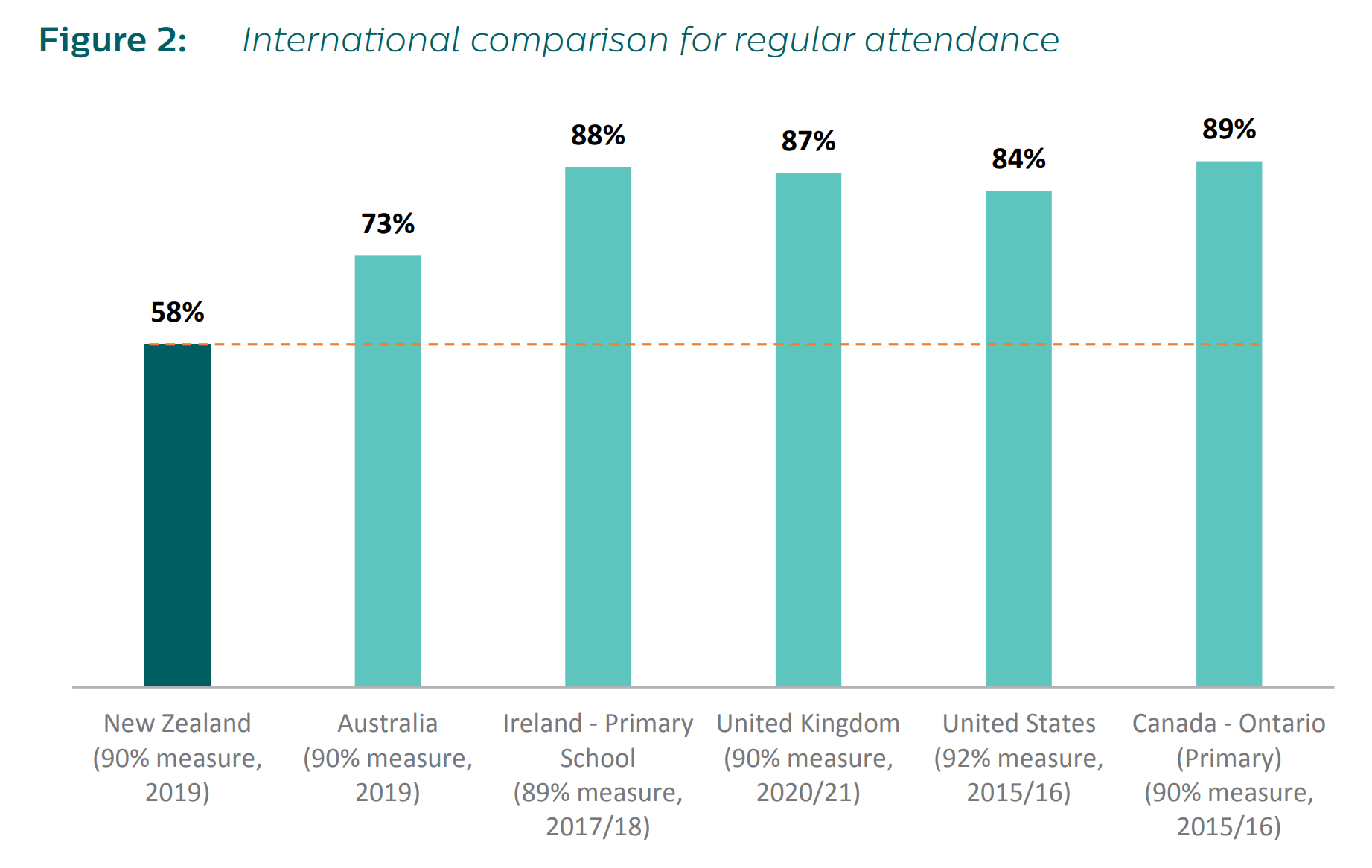

The last resort - when all interventions have failed, there are persistent unexplained absences, and the parent seems to condone them - is prosecution. Parents who don’t enrol their kids can be fined up to $3000. Parents whose kids don’t attend school can be fined $30 each day, up to $3000.18

Prosecution is very rare. The most recent data I could find is in the table below.19

Why is prosecution so rare? When it happens, does it actually work? This seems to be an area where, once more, there’s surprisingly little research. It appears that the education sector thinks prosecution is ineffective. However, anecdotal evidence suggests the threat of prosecution can work.20 A further factor likely limiting prosecutions for non-attendance is that schools have to pay for them. Schools are then supposed to be reimbursed by the Ministry of Education, but they don’t always trust the Ministry to do so.21

OK, once again we’re in ethically tricky territory. When things have gone so wrong a prosecution is considered, it’s hard to know how to right them: simple answers have long been exhausted. A 2018 prosecution illustrates the point.22

A Napier mother chose to keep her two kids, then aged under 10, at home. The mother would send the kids to school on the days they liked - for example, swimming sports - but not on others. This went on for two and a half years. The school, local agencies and local authorities went above and beyond to encourage the kids’ attendance. In the end, the judge found the mother had "cut herself off from a rational view", believing she was "in the right, that these children were best off at home". This meant "a prosecution was seen as the only way of bringing home to the defendant that she had fallen woefully short of her obligations as a parent."

In the end, the mother was discharged without penalty, the judge reasoning that to fine her would only be counterproductive.

It was supposed to be easier than this.

Remember me, the battleaxe mum? The one whose kids go to school, no matter what?

That's how confident I was: so confident I spotted the mistake in my kid’s report immediately. I wasn't troubled by it. Mistakes happen, after all. The school's been great, always, including for the ‘different’ kids; the neurodiverse ones who, if given the choice, would prefer the predictable comfort of bedroom to classroom. I simply rang the school to figure it out.

There was no mistake. The attendance data was exactly right. I'd had no idea.

The kaiarāhi was kind to me, and didn't judge; only explained in a gentle way that the more a kid goes to school, the better their life will be. I mumbled, I know, I do. I don't recall what else I said. I just remember the shame.

It was OK. It was always going to be. We have stable housing, food in the fridge, books and wifi, conversations about current affairs and our middle class aspirations; yet with all of these things - with all of them - my son had still missed a quarter of his schooling. In the midst of the worst of the pandemic, working long hours, drowning in the struggles of a miserable year in my personal life, I hadn't noticed a thing. Whatever answers I might have thought I had, well, I'd clearly flunked the hell out of this test.

I have never yet met the parent who didn’t want the best for their kid. For most of us, that means sending our kid to school: we know this, and we want to get it right. But to be a parent is like learning to drive. Knowing the seriousness if you f*** it up doesn’t make it any easier. You grip the wheel with your knuckles white, try to act like you’ve got this, and you hope for the best.

We all need different things as parents. Some of us need a helping hand to get our kids to schools. Some need confidence, a word of support, not to be looked at as ‘that family’. Some need space to figure out that intricate dance, parenting with kindness and with firmness when your kid is being tough. Some need to move quicker up the waiting list, for mental health or neurodiversity support. Some need kai for lunchboxes, a roof over their heads, a wage enough to pay for both. None of us need judgement, not ever.

And kids? Kids need the best support our society can give them. We forget, sometimes, that means supporting their parents.

He Whakaaro: What is the relationship between attendance and attainment? | Education Counts ↩

He Whakaaro: School attendance and student wellbeing | Education Counts ↩

Missing Out - Why Aren't Our Children Going to School (3).pdf ↩

The spreadsheet I took the data from is here: Attendance | Education Counts

Note that until a few years ago, the Ministry of Education collected only term two attendance data (not sure why) so I’ve used term two across each year for consistency. ↩Missing Out - Why Aren't Our Children Going to School - Summary.pdf ↩

He Whakaaro: How COVID-19 is affecting school attendance | Education Counts ↩

Covid 19 Omicron: School attendance rates in term 2 plummet to 40 per cent amid wave of sickness - NZ Herald ↩

03.-ER-Re-engaging-akonga-1270914-DCh-002_Redacted.pdf (education.govt.nz) ↩

Missing Out - Why Aren't Our Children Going to School (4).pdf

The data in this report is from this Select Committee report: Final report (Inquiry into school attendance) (5).pdf ↩

Education and Training Act 2020 No 38 (as at 24 August 2023), Public Act – New Zealand Legislation ↩

Making sure your child attends school – Parents.education.govt.nz – Practical information about education for parents and carers ↩

How Northland schools reversed declining attendance | RNZ News

Region where just 34% of students attend school launches truancy campaign | Stuff.co.nz ↩Truancy often the 'outcome of a bigger problem' | Stuff.co.nz ↩

Education and Training Act 2020 No 38 (as at 01 January 2022), Public Act 244 Offence relating to irregular attendance – New Zealand Legislation ↩

Rare truancy prosecution a case of 'last resort' | Stuff.co.nz ↩

Rare truancy prosecution a case of 'last resort' | Stuff.co.nz ↩

Rare truancy prosecution a case of 'last resort' | Stuff.co.nz ↩