The angry dudes got something right. We don't have one person, one vote.

Fuelled by grumpiness, I set out to explore claims that Māori have special electoral privileges. I discovered privilege, alright - but it's not for Māori.

Honestly, I meant to keep this post simple.

If you read the Facebook comments - and I don’t recommend it - you’ll find angry dudes insisting, ‘one person, one vote’. They’re convinced Māori get more votes than the rest of us and democracy’s at stake. I mean, no one can point to the rule that allows this extra voting, has ever seen anyone cast an extra vote, or can explain why the extra votes never show up in election counts. And yet.1

I felt like I’d set myself a straightforward assignment with this topic. I planned to figure out how exactly electoral stuff works, debunk a few myths, flip my hair and then go about my day. But the more I researched, the more layers I uncovered.

This myth that Māori get extra votes is curious. It seems to persist because it hits a nerve. That nerve is historical and cultural, running incredibly deep. I reckon this is the more interesting story, and it’s the one I want to have a crack at. Stay tuned.

First things first. Māori get the same number of votes as everyone else. Jesus wept.

This is the debunking bit. We’ll keep it brief.

Aotearoa has two electoral rolls: the Māori Electoral Roll and the General Electoral Roll. Māori can choose whether to go on the Māori roll or the general roll. The rest of us go on the general roll.

In a general election, everybody gets two votes: a party vote and an electorate vote. Folks on the Māori roll cast their electorate vote in a Māori electorate, and the rest of us cast our electorate vote in a general electorate. It’s much the same for local government. Folks on the Māori roll vote in a Māori ward (if their area has one), and the rest of us vote in the general ward we live in.2

There you have it: everyone gets the same number of votes. And importantly, every vote has the same power. All electorates have about the same number of voters, and all wards in a given place have about the same number of voters. This means each person’s vote has about the same impact on the election result, whether they’re on the Māori or general roll.3

Not very exciting, is it? Maybe you came here expecting some kind of exposé or scandal, and all you got was maths. Sorry. The Māori roll is perfectly compatible with the ‘one person, one vote’ idea that underpins our democracy. So why are people losing their shit?

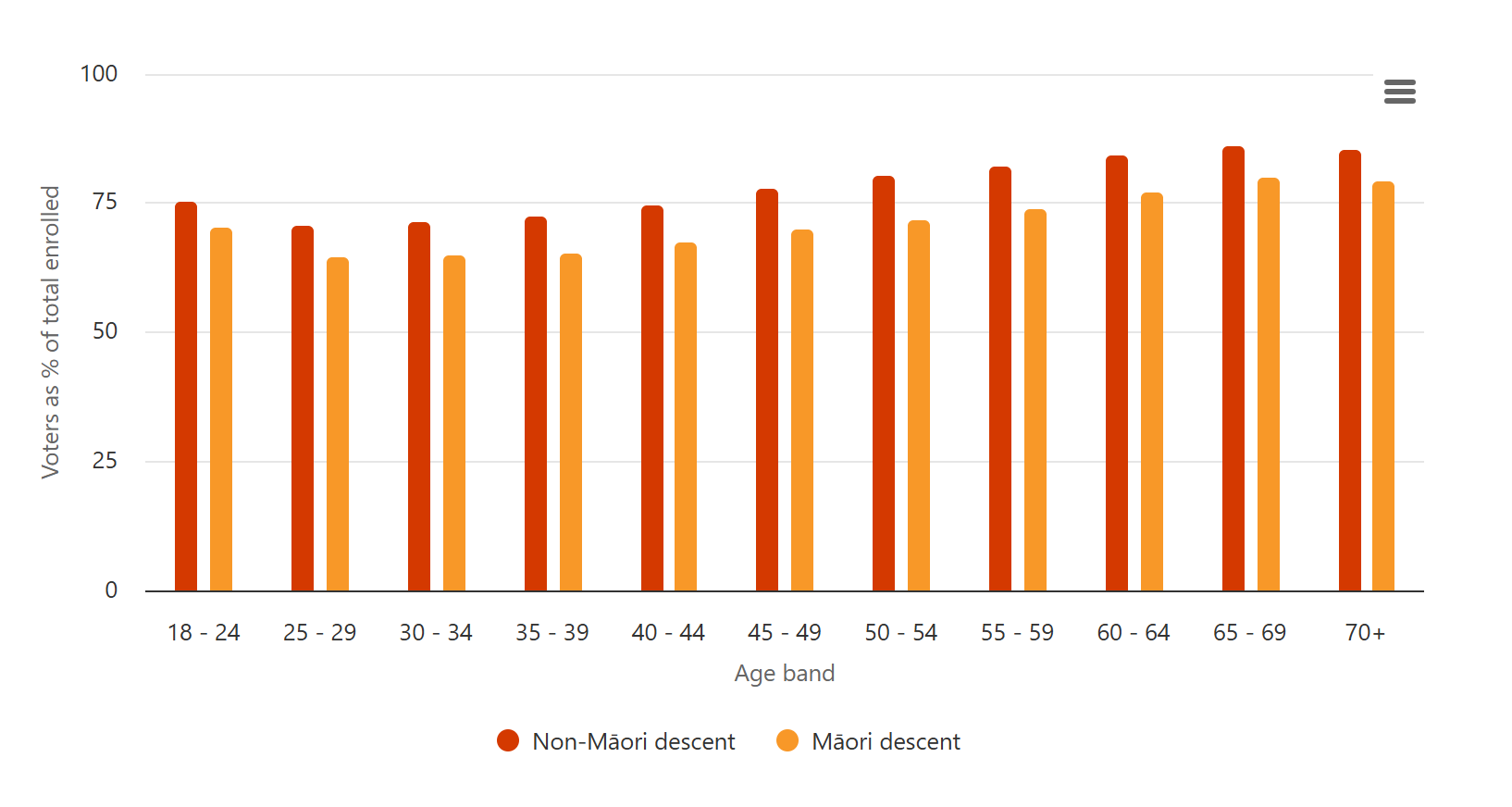

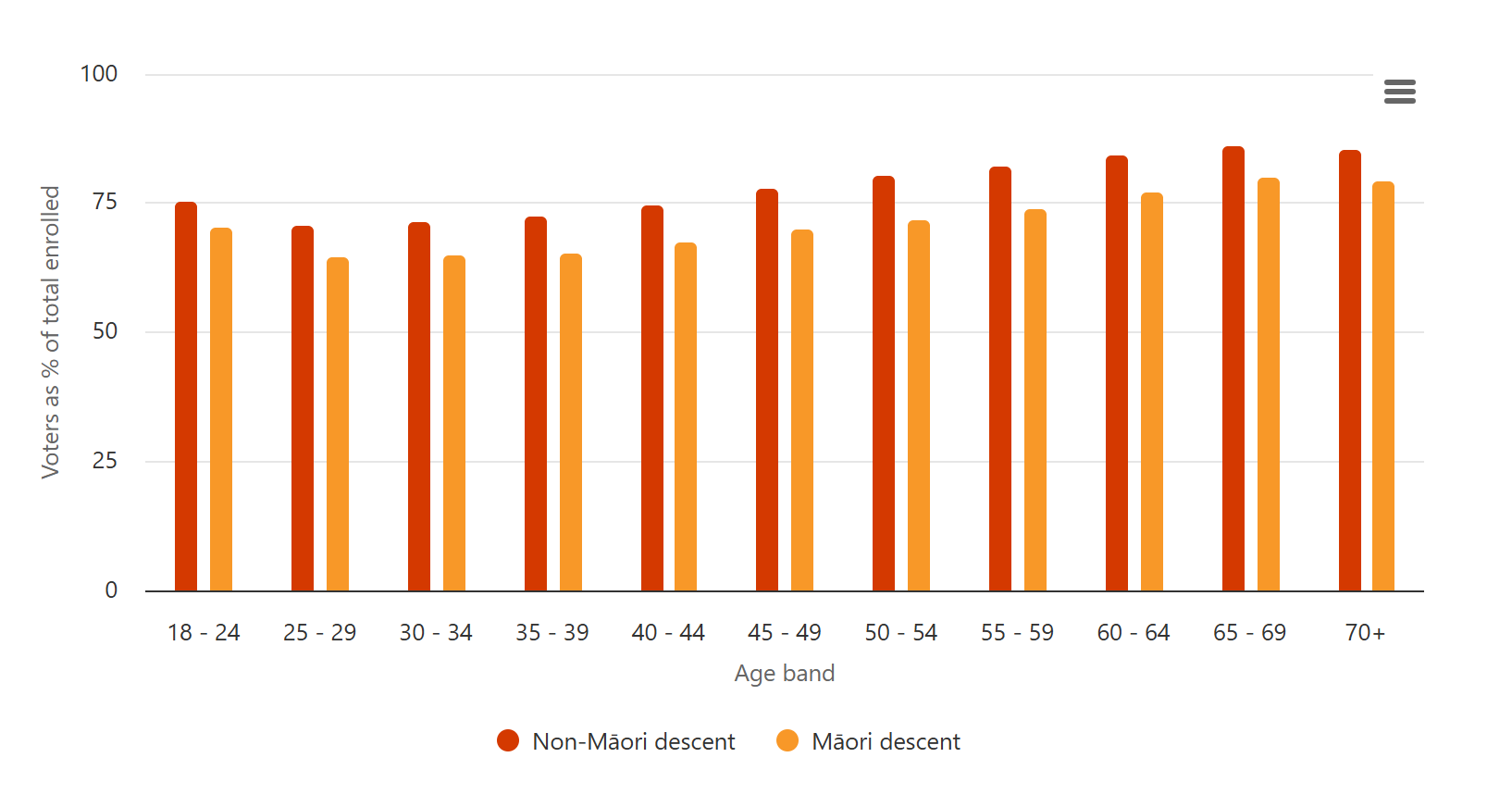

As we’ll see, there are lots of reasons, but the obvious one is this. The point of the Māori roll is to guarantee at least some Māori get elected. There’s also some evidence the Māori roll encourages Māori voter turnout, which is lower than the non-Māori turnout.4 Some people don’t get this, and think it all means extra votes for Māori. Some do get it, and think it’s extra privilege for Māori. But as we’re going to see, our electoral system has always guaranteed Pākehā will be elected. If that ever changed, and democracy stopped serving up Pākehā majorities, you wonder if the angry dudes might decide ‘one person, one vote’ isn’t the best system after all.

Anyway: we’ve seen what the Māori roll is meant to achieve. What’s actually happening? Māori make up about 17% of the population.5 Are we seeing Māori in about 17% of elected positions?

Actually, it’s a good news story. About 27% of MPs are Māori.6 Local government data is harder to find, but it seems about 20% of local representatives are Māori.7 In time, this will probably mean a conversation on evolving our electoral approach, and the best way to do te Tiriti together in a changing world - a conversation that could be positive, if we’re not dicks about it. More on this later.

You’ve stuck out the maths part of our story: good job. Think of it like you ate your vegetables, and now you get pudding. Let’s turn to some history instead.

What’s this obsession with ‘Māori privilege’?

Okey dokey. We’ve seen there’s a myth that Māori get extra votes. The myth persists, even though it’s a bit bonkers. Why?

The short answer, racism, didn’t satisfy me. Fossicking for more, I discovered the work of an academic, Professor Peter Meihana of Massey University. A fascinating guy, Meihana developed vitiligo, a condition that lightened his skin colour, as a young adult - meaning the world treated him as Māori when he was a kid, then Pākehā afterwards. With an intimate understanding of the way privilege works, he wrote a PhD on the topic. Meihana points to some key moments in our history that set the Māori-are-privileged myth in motion. I’ll paraphrase a bit, and any shortcomings are my own.8

First, there was the arrival of Captain Cook in 1769. Cook turned up not just with a ship and a crew and a jaunty wig, but with a European way of looking at the world, including the idea that races are a hierarchy. In his mind, indigenous people could never be as good as white people, but some indigenous folks were still better than others, depending on how similar they seemed to Europeans. Māori weren’t the best - Tahitians took that dubious honour - but in Meihana’s words, Cook saw them as ‘a different type of savage than, say, the Aborigines of Australia’. After all, Māori had agriculture, which put them ahead of hunter-gatherers.

This middling score on a racial league table was thought to make Māori privileged.

Added to that, the competition to carve up the world - the enterprise that Cook was part of - was starting to change at the time Aotearoa was colonised. By the 1830s, the British were beginning to think of themselves as the nicer colonisers, and therefore the ‘rightful leaders’ to teach and protect and civilise indigenous people.

Māori got the self-appointed nicer colonisers. Privileged again.

The rest is history. I’m not saying it was a simple story of good guys versus bad guys, or good faith versus bad faith, and I’m not sure Meihana’s saying that either; but our record of colonial dispossession speaks for itself. The Māori privilege myth has been a stubborn part of that record, resurfacing especially at tense political moments.

You can hear Susie Ferguson interview Meihana about his work on RNZ. Listeners text in their feedback for Susie to read out. One texter insists that Māori needed te Tiriti as a way forward following the musket wars - a confident bit of explaining, given Meihana is a literal history professor. Another texter simply moans that talking about Māori privilege is woke.

Listening to the interview brought something home to me. ‘Privilege’ of the type we’re talking about is supposed to be met with gratitude. You could say it establishes a kind of debt. When someone gives you something - even something you already had, or something you never wanted - you’re meant to be smile, not point out problems. What we call Māori privilege is about feelings as much as rules, no matter how confidently some guy explains it in his text.

On air, Meihana answers the texters with patience and grace. You can tell he’s heard these arguments before.

What’s the ‘one person, one vote’ backstory?

Let’s recap. We used maths to debunk the myth that Māori get extra votes. We looked at history to figure out how a myth like that sprung up in the first place. But we haven’t really dug into ‘one person, one vote’ itself, or the group of concepts it’s part of. Now it’s time to try our hand at political philosophy. Fancy.

We saw how Captain Cook arrived in Aotearoa with a European way of looking at the world based on a racial hierarchy. Europeans had a lot of other ideas too. We can summarise some of these ideas as package deal called ‘liberal democracy’. Great minds have written on this topic, and lord knows I’m not one of them. Still, we can make a few comments.

Once upon a time, Europe was a shit show: all-powerful monarchs, unfair taxes, peasants driven from their land and opponents’ heads chopped off. (Yes, we’re generalising extensively.) There had to be a better way. Over time, people came up with the concepts of property rights, political rights and civil rights.9

How did that pan out? Well, in theory at least, everybody was now equal. Elected governments became a thing, rather than monarchs only, and everyone got given the same political power, including the same right to vote. People’s property couldn’t just be taken away anymore, either by other people or the government. Instead, people had to exchange stuff and deal with one other by making contracts - agreements they had to keep, and which could be enforced through laws. And laws were meant to apply to everyone, powerful or weak, in exactly the same way. Again, in theory, this ended discrimination.

People both inside and outside European cultures have criticised the liberal democracy package deal. It’s all about individuals (not collectives). It cares a whole lot about economics (and not so much about non-material values or the planet). And it has a funny old way of upholding the powerful over the weak when push comes to shove. But there are good ideas in there too, and the package deal was better than the shit show that went before.

Why then do we need to be cautious?

The first reason is kind of obvious. You can’t pick up a system from one side of the world and plonk it down on the other without expecting it’ll need a tutu.

The second reason is more subtle. Politicians often push back on Māori rights and claims with liberal democracy words like ‘human dignity’ and ‘universal human rights’. These words don’t just shut down other perspectives, implying there’s only one way any reasonable person can think. The kicker is the contrast this thinking sets up. Human dignity versus degradation. Universal human rights versus arbitrary power. Progress versus backwardness, enlightenment versus darkness. You know, coloniser versus colonised. It’s a tactic, as much about feelings as rules - and it’s designed to push buttons you didn’t even know you had.

For what it’s worth, so-called Māori privilege actually fits fine with the liberal democracy package deal, if you want to look at it that way. Customary rights are the property rights Māori had before Europeans arrived. The Treaty is a contract. Even ‘privileges’ that angry dudes tend to go on about, like the different tax rate for Māori authorities, are explainable as sensible policy.10

But as we’re going to see, the liberal democracy package deal, including ‘one person, one vote’, doesn’t always live up to its own hype.

If ‘one person, one vote’ is that awesome, why didn’t we bloody do it?

OK, we’re going back for a bit more history. Captain Cook turned up, followed by more Europeans. They brought with them the liberal democracy package deal, including ‘one person, one vote’. Te Tiriti was signed in 1840. A Parliament was established, and in 1853 Aotearoa had our first election. What happened next is much stranger than I realised.11

At first, Māori men had the same rights as other men: they could vote if they owned property. By colonial standards, that seemed like a good deal. But there was a catch. Men had to own property individually to qualify to vote, and Māori tended to own land collectively (annoying settlers, because collective land was trickier for Pākehā to buy).

No one minded too much - Māori didn’t want to vote, and Europeans thought they shouldn’t anyway - until 1867. With all the warring that had been going on, Pākehā thought Māori needed to be assimilated, and voting seemed as good a way as any. To get around the faff created by the property ownership rule, Parliament said sod it: all Māori men 21 and over should get to vote (even before all Pākehā men could). But there was a catch. Māori men got four seats across the whole country, and bugger all influence: the Māori seats had way more voters than the European ones.

These were the first Māori electorates, and the idea was they’d get phased out once Māori stopped holding out against individualised land ownership. That was meant to happen quickly, but didn’t. In the meantime, Māori got into the democracy thing, pushing for a fairer deal.

As we all know, women got the vote in 1893 - and that included wāhine Māori. You’d think this would’ve been a game changer, but nope. The Māori voting system was legally separate from the Pākehā system (although so-called ‘half-castes’ could choose which system they preferred). The Māori system was also crappy. Māori voted at a different time to Pākehā, sometimes weeks later. In 1870, Pākehā got the right to a secret ballot, but Māori had to rock up to a polling place and tell an official who they wanted to vote for, right up until 1938. It wasn’t until 1967 that the law was changed so that Māori could stand in European seats. It wasn’t until 1996 - the first election I voted - that the Māori seats increased from the original four.

All this was brought to you by the liberal democracy package deal, and its ‘one person, one vote’ mantra - ideas so awesome that Europeans had exported them around the world for the benefits of the colonised. The trick was this. ‘Universal human rights’ have an out clause. You just define some people as a wee bit less human.

This hurt is within living memory. So, surely, is the mistrust it engendered.

Still, this is all history. We eventually realised that ‘one person, one vote’ means exactly that, and we edited out the parts of our past that didn’t fit. Was the problem solved?

The problem was not solved.

Now we reach the present day. Maybe the journey was bumpy, but ‘one person, one vote’ is a thing, isn’t it. If there was any trace of different treatment left in our electoral system, those angry dudes would find it out and complain, right?

Right?

In August last year, the Government changed the law. This means councils who’d established Māori wards from 2021 onwards either had to hold a referendum on them - or pre-emptively dump them instead. But councils have kept their powers to create rural wards for underrepresented rural people.12 That seems inconsistent.

Radio silence from the angry dudes.

But I offer you a nuttier example. Inexplicably, Aotearoa shas something called a ‘ratepayer role’. In local elections, everyone can vote in the place they live. But if you own property in another area, you can also apply to cast a vote there.13 The more places you own stuff, the more votes you can get. In 2016, some guy enrolled to vote for no less than eight different Auckland Council community board elections.14

Is this some kind of archaic rule that’s just slipped through - even as Māori have spent about a century and a half fighting for electoral justice? Nope. In 2024, Labour’s Greg O’Connor brought a member’s bill to repeal the ratepayer role. The coalition parties voted it down.

Yep. We’ll tweak the rules of democracy for baches and boat sheds but not tāngata whenua. It’s shit - and yet so honest about our true cultural values that it’s kind of refreshing.

What do the past and present teach us for the future?

Let’s finish with one last story.

Rotorua - as we know it today, at least - was founded on 25 November 1880. Everyone could see it was an extraordinary, beautiful place. Francis Fenton, the chief judge of the Native Land Court, had an idea, and he called local iwi together to discuss it. With a bit of collaboration, they decided together, Rotorua could become a tourist mecca.

The plan went like this. Iwi would gift land to the Crown for railways, hospitals and amenities. The Crown would control the town’s thermal waters. Māori would continue to own other land, but would rent it out through 99-year leases, attracting businesses.

Everyone agreed; but soon after, things started to unravel. Tarawera erupted. The economy went sour. Construction of the national railway was delayed. Leaseholders went belly up, and prosperity slipped through the town’s fingers. What was known as the Fenton Agreement had failed, and the losses were eyewatering - but the pain wasn’t shared equally. In a breach of contract, iwi were forced to sell the leased-out land to the Crown. In the decades that followed, the Crown then onsold some of this land to private buyers. Iwi kept asking for answers. The door was shut in their face.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the Crown recognised the breach of contract and began to make good.15

In 2022, under the previous government, something called a local bill was introduced to Parliament. It was called the Rotorua District Council (Representation Arrangements) Bill, and it sought a rule change that would let Rotorua elect councillors differently from other local bodies. Essentially, the bill deliberately departed from ‘one person, one vote’, because it aimed to give Māori roll voters more seats than their proportion of the electorate. It was partly an attempt to make up for the injustice the iwi had endured.16

The bill started out strong, but its support soon dwindled. The then-Opposition were strident against it. And the Attorney General, Labour’s David Parker, had concerns. Sometimes, he said, going against normal human rights can be justified - but Parker wasn’t convinced this situation hit that threshold.17

In the end, the council itself got cold feet. The bill died in the context of the wider turn against co-governance - a term we never really defined, using ever more widely, and with ever more disparagement, to refer to anything Māori.

If I’m honest? I don’t know that the bill’s approach was the best way through. ‘One person, one vote’ is still an important value. At its best, it safeguards the weak from the powerful - even if it’s seldom at its best. But I figure that if I don’t like one idea, I’ve got a democratic responsibility to help bring other ideas to the table.

In Rotorua, as across the motu, the liberal democracy package deal has had a way of failing the same ‘privileged’ people every time. Still, our leaders stand by the rules.

Because everyone likes the rules when they’re winning the game.

Thanks for supporting my mahi! Subscribe to The End is Naenae, and I’ll see you next time.

No, you don't get an extra vote if you're on the Māori roll ↩

As well as wards, there are also things called constituencies, depending on the kind of council. But that’s too many words, so for our purposes we’ll try to keep it straightforward. ↩

It’s a little bit trickier than that, but that’s the gist.

About Māori wards and constituencies - Vote 25 | Pōti 25

Working out how many electorates there should be | Elections ↩

If you enjoy a faff with a graph, have a play with the data on this webpage: Voter turnout statistics | Elections

Law change prompts spike in Māori electoral roll registrations | RNZ News ↩

Record number of Māori MPs elected to New Zealand Parliament - New Zealand Parliament ↩

I’ve done the maths in bit of a crude way, because that’s the extent of my maths-ing, but I think it’s OK for our kōrero. If you want better maths-ing, have a look at the Jack Vowles article below, noting that it’s a bit outdated.

What you need to know about Māori wards | RNZ News

Local government’s Māori representation gap | News | Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington ↩

Peter Meihana: putting privilege in check | RNZ

Peter Meihana: The pervasive myth of Māori privilege | E-Tangata ↩

See the article below. The Māori authorities tax rate is low at 17.5% for entirely good reasons. The land it applies to might have a commercial use, but is also likely to have spiritual and cultural uses (so isn’t making much money). The land may have been returned through a Treaty settlement, so it doesn’t make sense for the government to give with one hand and take with the other. And because most of the beneficiaries of the land have really low incomes, the 17.5 tax rate is about right. If the government taxed the land at a higher rate, it would only have to do a shitload of work to then reimburse the beneficiaries for the amount they’d been overtaxed. And that would cost the taxpayer. Be sure to pass this information on to anyone you believe needs to STFU.

Muzariri & Adams [2020] 7 Te Tai Haruru: Journal of Māori and Indigenous Issues ↩

One person, one vote: Abolish the ratepayer roll - AUT News - AUT ↩

'Archaic' law allows multiple-property owners extra voting rights | RNZ News ↩

The Fenton Agreement 1880-2030 - Rotorua Museum

The Fenton Agreement The Contract That Created Rotorua - Holland Beckett Law ↩

Rotorua District Council (Representation Arrangements) Bill — First Reading - New Zealand Parliament ↩

Rotorua council representation bill: Labour backs council's delay | RNZ News ↩