This one goes out to all the dropkicks

Some people in this life have their shit together naturally. They are not dropkicks.

My sons are two of those people, and their brains fascinate me. They’re neurodiverse, and that comes with its quirks and limitations - but both have an intuitive drive to map stuff out, everything plotted according to place and time, cause and effect, their own location amongst all these factors carefully identified. By coincidence, I’d said to my younger son the other week, ‘We need to get you on the electoral roll’. He gently explained he’d done it himself a year before, at the time he’d turned eighteen. (I felt a bit redundant as a parent, but I had to give full credit to the fella who laid me off.)

I too have my shit together - but in my case, it was a hard won victory, and the peace is fragile. Here’s what goes on in my noggin. What do you mean, my lost glasses are on my head? How the hell was I meant to know my annual WoF is due, only a year since the last one? And did I switch the stove off, or did I imagine it? Did I go downstairs and check it was off, or am I getting confused with yesterday? Or did I mean to check, but then I forgot why I was there and did something else instead?

You get my drift.

I manage my quirks with a system that serves me well: lists with colour codes and deadlines and priority rankings. But there are some things a list won’t overcome. The chink in my armour is my trouble with clocks and time-related stuff more generally. I can’t even explain what’s happening for me cognitively, but I misread my calendar frequently, so I’ll double-book or not turn up - and I often miscalculate the time between two points. For example, if it’s 9:45am and I’ve got a 10:30am deadline, my brain will tell me I have an hour and a quarter to get things done. Needless to say, this sometimes ends badly.

Life circumstances can overturn my brain’s fragile peace. By way of example, 2023 was one of the shittiest years I’ve ever had. I had to prep the family home for sale as part of a separation (everything that could’ve gone wrong did), put all our stuff in storage except a few bags, share a friend’s basement bedroom with my younger son for three months while we were between homes, then take possession of our new house. I was desperately sick with long COVID. It was all I could do to survive the workday: there was nothing left of me cognitively after 5pm. Looking back at that time, I made some shocking boo-boos.

Days before we moved out of the family home, I still hadn’t organised us anywhere to live. I knew I was in a mess, but I didn’t have the mental functioning to fix it. My worried younger son, still a schoolkid, tried to sort things out, researching Airbnbs and bringing me options. Soon after, I was nearly taken in by a ham-fisted text scam because I didn’t have the brainpower to recognise it. And when we made it into our new house, I had perhaps my worst bungle. I botched the set-up of an automatic payment, meaning my home and contents were uninsured - something I only picked up by chance. A list won’t help you if you don’t have the wherewithal to make one: that was me. It seemed like I was paralysed by an inability to help myself, and in my worst moments I felt vulnerable and useless and ashamed.

I was a dropkick, eh?

These are mostly middle-class problems. I always knew things would get better, which is the ultimate difference between the haves and the have nots. So I doubt I’m the flavour of dropkick David Seymour had in mind the other day. He was commenting on the just-announced change to electoral rules, meaning people will need to enrol in advance of the election period, not at the point they turn up to vote. If they don’t enrol in advance, they’ll miss out on voting. Critics say the rule change will catch out Māori and Pasifika, young people, and those in unstable housing. Seymour responded to critics’ concerns like this: “Frankly, I’m a bit sick of dropkicks that can’t get themselves organised to follow the law”.1

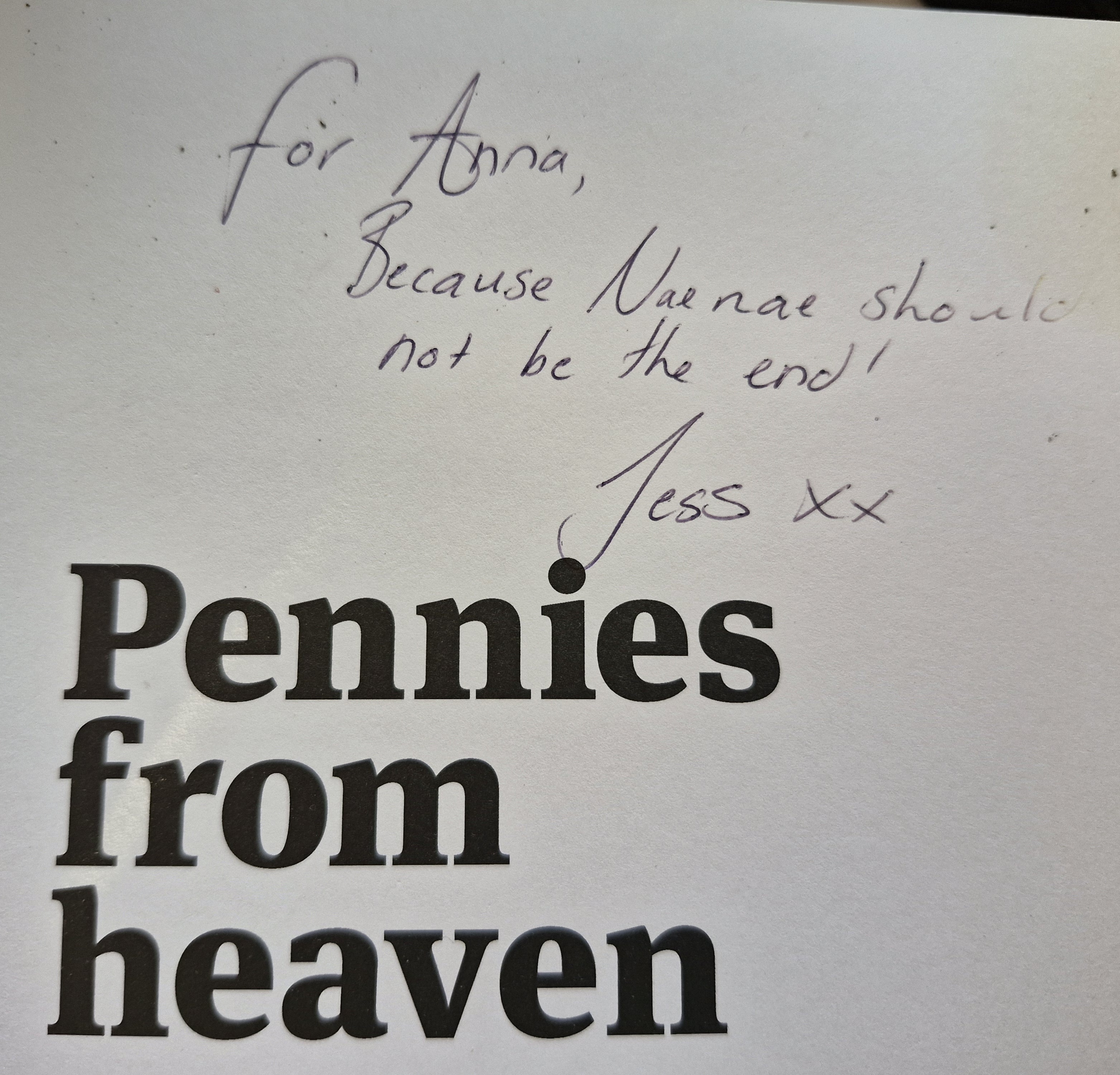

Hmm. There’s a lot that could be said from a great many angles; but when I heard Seymour’s remark, I remembered a 2017 book written by my friend Jess Berentson-Shaw, called Pennies from heaven.2 It’s rigorously researched and surprisingly easy to read, and it asks what it would take for every kid in Aotearoa to thrive. To be clear, Pennies from heaven isn’t directly about whether people have their shit together, or why not. But I’m going to share a few ideas from the book - and then I’m going to explain why I think these ideas relate to Seymour’s ‘dropkick’ comment and the assumptions behind it. The language is mine, and so are any errors (sorry Jess).

Pennies from heaven is interested in a bunch of things, including why kids raised poor often end up poor as adults too, with all the challenges that being poor can entail. This is a political question as well as a scientific one. If you see poor people as dropkicks, you probably put their poverty down to bad personal choices (you think they just ‘can’t get themselves organised’). And you probably have very little sympathy: you reckon folks should just know better and choose better.

But is it really that simple? Well, no. Pennies from heaven looks under the hood for a better explanation.

The first idea that Pennies from heaven tests is called the ‘investment pathway’. At first, this idea seems completely intuitive. Being in poverty means whānau are lucky if they can afford rent, power and food. High quality early childhood education and other learning resources are simply off the table. Children don’t do so well academically, and that carries all the way into adulthood, including the ability to get a job. But maybe surprisingly, the investment pathway has the least evidence, even though it’s politically popular - maybe because it seems to offer a straightforward answer, just do better at school.

The next idea Pennies from heaven lays out is the ‘family stress pathway’. Poverty creates stress, depression and conflict for adults. This affects how well they can parent, and ultimately how their kids grow up. This pathway has good evidence to support it, but it’s still not the whole story.

It’s the third pathway that really gave me pause for thought. I’ll spend a little more time trying to explain it - and when I’m done, you’ll understand why I think it matters to how we understand and judge people’s shit-together-ness.

The third pathway is called the ‘toxic stress pathway’. Poverty creates all kinds of stresses - not just because you’re going without the things you need, but because you’re feeling like you’re at the bottom of a social ladder, with others looking down on you. Because you’re poor, bad stuff like unemployment is more likely to happen to you - and you’re also less likely to have the resources to ride the bad stuff out. The ‘fight or flight’ response that other people feel only sometimes - with its flood of stress-related body chemicals - is your constant state. It’s hard to imagine anyone making their best decisions feeling that way.

But that’s not where it ends.

Stress from parents also makes its way down to kids - not just because kids do worse in education, or because parenting is harder for the adults, but because stress from poverty enters children’s brains and bodies. This is called ‘biological embedding’. Research involving brain imaging of children has found that poverty affects cognitive development by changing actual physical structures: even small differences in family income are associated with big differences in the surface areas of kids’ brains.3 Kids’ immune systems and metabolism are affected too. They grow up more likely to die from a host of causes: cancer, coronary heart disease, strokes and respiratory issues.

The message of Pennies from heaven is ultimately one of hope. Each of the pathways we’ve talked about can be altered; and not by anything particularly revolutionary or even tricky, but just with better family incomes. And brain development isn’t all-or-nothing either. Our brains get more rigid over time, but they can still be changed: it just takes work and resources. If we can complain that individuals can’t get themselves organised, maybe we should get our shit together at a societal level too.

Because ours is a society that heaps toxic stress, and its effects on decision-making, onto people. This is not a bug, but a feature.

Stress comes in all forms. I know people who are caring for sick and elderly parents, raising kids with health needs, or doing both at once. I know people who are losing their jobs or picking their lives up after divorce. I know people managing mental health stuff or addiction. I empathise with all of them. Am I the type of person who’d forget to enrol to vote? No. But if you’d asked me a couple of years ago if I’m the type to let my insurance lapse, I would’ve said no to that too. Each of us is only one serious enough life event away from not having our own shit together.

But we reserve the worst, most paralysing toxic stress for the ones with the least ability to withstand it. The ones who don’t know whether they’ll be living in the same place three months hence, because we value a landlord’s easy capital gains more than a family’s security. The ones who don’t have work, or who can’t pay the bills with the work they’ve got, because we claim to value hard mahi, but we don’t care to pay much for it. The ones who never know whether they’ll get an unbroken night’s sleep, or another trip to ED with a child who can’t breathe - because healthy homes mean compliance costs, but holes in the lungs of babies are free.

For some people, toxic stress is all they’ve known since they were children, and all they’ll ever know: an inheritance of brain and body that will pass to their own kids. And we wonder - we have the barefaced audacity to wonder - why getting themselves on the electoral roll quite fast enough isn’t everybody’s top priority.

I’ll leave you with a final story. It’s about a time I didn’t have my shit together - or maybe I ultimately did. You can judge.

Years ago, I was a manager working in a big organisation for a particular senior leader. I was hellishly busy with a giant workload, trying to deliver good quality mahi and look after my team along the way. For the most part I hung in there, juggling everything, my colour-coded list always to hand. But one day I messed up, because mistakes happen under stress. I slightly missed a fairly unimportant deadline. To this day, I’m not sure what went wrong, but I think my brain pulled its signature move and I misunderstood the clock.

The senior leader could’ve cut me some slack - she knew I was hardworking and conscientious - or just spoken to me privately, but she was always kind of mean. Instead, she sent a reply-all email detailing her disappointment with me. The email was intended to belittle me, and at first it did. It took me back to school, and even my first attempt at university, when I could be the dopey one, the drippy one, the clock mis-reader, the deadline-forgetter, the last-minute panicker, the girl whose dropkick moments could leave her confidence so low she found it hard to speak in class. The girl who thought she was just a bit stupid, but who only needed time, understanding, and the power of a colour-coded list to get her shit together.

I realised the shame I’d been carrying, and I realised it was time to set it down. And so I did. I finished the thing that had missed the deadline, carefully printed and stapled it, and found out the senior leader. I knocked politely, waited for her permission to enter the room, handed her the papers, and then growled her. I growled her. I growled her unencumbered by a single f***, which is coincidentally the same number of f***s I give to this day. And she just blinked at me with surprise, not knowing quite what to say or do, because she’d been GROWLED.

I am more than my moments of my shit-not-together-ness, and on a good day, my brain is beautiful. Whether it’s a good day or not, I am worthy of respect. However your brain works, and whatever your circumstances, you are too.

Dropkicks may not always be elegant, especially panicked ones just before the full-time whistle, but they can still win matches.

One dropkick to another: subscribe to The End is Naenae, paid or unpaid, and we can hang out more.